Block Withholding Attack

Disclaimer: All the image in this post is uploaded to sm.ms, which may not be friendly to readers in mainland China.

PoW Mining Model

As we all know (?), in PoW (proof of work) blockchain system, miners can mine blocks to gain block reward (bitcoins). Mining blocks requires the miner to prove that they have done a certain amount of work. The most common proof of work is to find a hash that satisfy certain properties. For example, the hash value of a string in integer is no larger than a certain number $N$. Assume the range of the output of hash is $R$, then the probability of a random hash to be valid will be $\frac{N}{R}$.Due to the nature of cryptography secure hash functions, the distribution of output hash is unpredictable given any different strings as input, which means we may assume that the probability of any string to has a valid hash is $\frac{N}{R}$. Note that there can be other means of constrains for a block to be valid, but the core is simple: the probability of a hash to be valid will be $p$, which is typically a small number.

Let’s take a look at a well-known real-world example: Bit-Coin. In Bit-Coin, the threshold $N$ is related to difficulty. Trivially, the higher the difficulty is, the lower the threshold will be. This is threshold is adjusted dynamically by the system in response to the overall computing power in the Bit-Coin mining system. It’s public to all and can’t be configured manually. This is not the core of this blog post, so we will skip on this.

Why do we need a mining pool?

In short, Bitcoin’s security relies on proof-of-work: miners construct block headers (including a nonce and transactions) and hash them with SHA-256. A block is valid if its hash is below a global difficulty target (equivalently, starts with $z$ leading zero bits). Finding such a hash is probabilistic and computationally intensive. A solo miner with fraction $\alpha$ of the network’s total hash power will on average mine $\alpha$ fraction of the blocks over time.

Since the difficulty of Bitcoin is dynamically adjusted to maintain an average block interval of around $T = 10 \text{min}$, a solo miner finds a block every $\frac{T}{\alpha}$ on average.

As finding a valid hash (i.e. starts with $z$ leading zero bits) is random, we may assume the probability density function of finding the first block at time $t$ is modeled by exponential distribution $f(t)$.

Suppose $f(t) = \lambda e^{-\lambda t}$. Since $\mathbb{E}(t) = \frac{T}{\alpha}$, we have $\lambda = \frac{\alpha}{T}$.

- The variance of $f$ is $\sigma(f) = \frac{1}{\lambda} = \frac{T}{\alpha}$

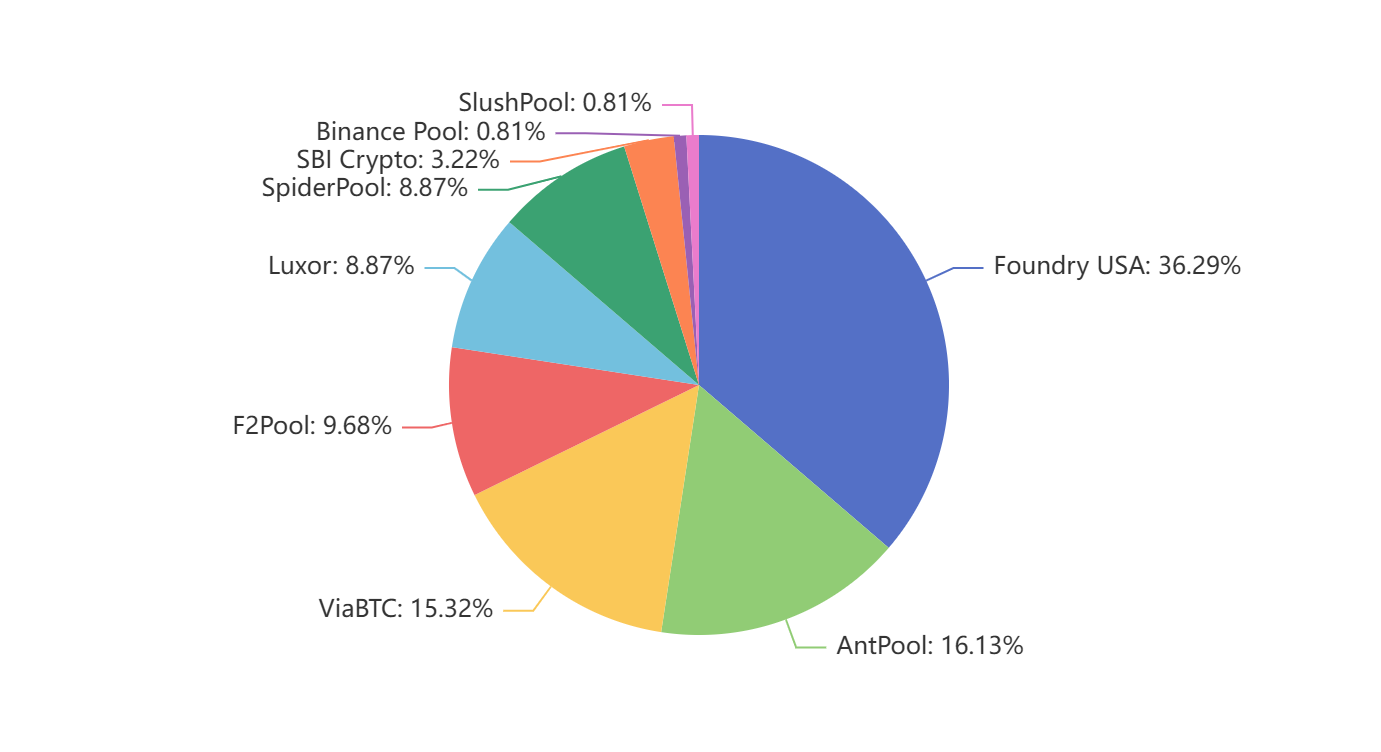

However, $\frac{T}{\alpha}$ may be prohibitively large for solo miners. Currently, the overall computation power in Bitcoin mining has reach around $800\text{EH/s}$, which is $8 \times 10^{20}$ hash per second. For a 3090, a common GPU for personal computer, the peak hash power is less than $200\text{MH/s}$, which is $2 \times 10^{8}$. Even for designated ASIC hash machines, their peak hash power can only reach $1000\text{TH/s}$, which is $1 \times 10^{15}$, still orders of magnitude lower.

What is a mining pool?

While $\frac{T}{\alpha}$ can correspond to years — or even decades — for a solo miner, this level of delay is typically infeasible. A practical solution to mitigate such high variance (and the associated financial risk) is the mining pool.

In a mining pool, coordinated by a pool operator, each miner performs a share of the total computational. Although only one block will be valid in a round, and only that valid block will make a profit, the miner will evenly distribute the reward $R$ of block to each miner, judged by each one’s contribution.

The rationale is intuitive: the more work a miner contributes, the more reward they receive. More importantly, participating in a pool significantly reduces the variance in individual earnings - a point we will analyze in more detail two slides later.

In real-world, it’s infeasible for a mining pool to distribute its income by each one’s real work: it would take equal time to verify the miners submit a nonce with its corresponding hash value.

To address this, miners do not submit every hash they compute. Instead, similar to Bitcoin’s global difficulty mechanism, miners submit selected (nonce, hash) pairs - known as shares, that satisfy:

- Correctness: $H$(nonce + transaction) = hash

- Difficulty’: hash starts with $z’$ zeros.

The value of $z’$ is determined by the pool operator and satisfies $0 \le z’ \le z$, where $z$ is the global difficulty. A lower $z’$ allows miners to find shares more frequently, while a higher $z’$ reduces verification overhead for the pool. Pool operators thus choose $z’$ to strike a balance between efficient mining and manageable validation cost.

So why is the variance reduced? Because the effective difficulty for submitting shares is significantly lower. As a result, miners can find valid shares more frequently. The new expected time to submit a share becomes: $\frac{T}{\alpha} \times 2^{z’ - z}$.

In practice, mining pools also incur additional overhead. For example, verifying (nonce, hash) pairs requires computational resources, and maintaining the pool server infrastructure adds operational cost. To cover these, pool operators typically take a small portion of the block reward $R$. As a result, the miner’s expected reward per block may be reduced to $\lambda_1 R$ where $0 \le \lambda_1 \le 1$.

Ultimately, this creates a trade-off: miners gain more stable and predictable returns (lower variance), but at the cost of slightly lower expected rewards. To fight alone or along, which is the right way…

Next, we will discuss block withholding attack (BWH) on mining pool.

Why there are Block Withholding attacks?

Not all the miners are honest. Some selfish people may think: Why do I need to submit a valid block to the pool operator? As the reward now is only judged by shares that one submits, one can refuse to submit shares that can be a valid block.

Although this seems to reduce the average reward per time unit for that miner, the malicious miner may have some compute hash power outside, which may take advantage. In other words, the hash power of a malicious miner can be divided into 2 (and even more) parts: one for dishonest mining, one for mining in other pools or solely. The second part may benefit from undermining the first part.

As long as the gain from sabotage > loss of withheld rewards, a rational (but selfish) miner may choose to attack.

Even worse, some mining pools may deliberately encourage such malicious behavior. Since undermining other pools can bring competitive advantages, these evil pools may choose to reward attackers who successfully perform block withholding attacks against their rivals.

To prove the attack, a malicious miner only needs to show evidence that they found a valid block while mining for another pool, but intentionally withheld it. For example, they can submit the nonce and corresponding hash of that valid block to the sponsoring pool.

This strategy is known as a sponsored withholding attack. It significantly worsens the problem, turning individual dishonesty into a systemic threat, and may incentivize more miners to engage in block withholding for profit.

Now, we will prove that BWH may indeed benefit the 3rd-party, and how malicious can benefit from that.

What benefit does BWH bring?

For simplicity, suppose there are only $3$ organizations: 2 public pools and 1 sole miner. The hash power fraction of first pool is $p$, and the hash power fraction of second pool is $p’$. The sole miner’s fraction is $\alpha$ and we have $p + p’ + \alpha = 1$.

Suppose the reward proportion distributed to each from a single pool is $\lambda_1$, which means the pool will keep $1 - \lambda_1$ of the block reward. Suppose reward $R = 1$.

We assume the sole miner is malicious, and $\beta$ of his hash power is used for attacking the first pool, which is $\alpha \times \beta$.

Gains of the 3rd party

First, we will show that BWH can benefit the 3rd-party.

Without any attack, the gain rate of the second pool is $\frac{p’}{1} = p$. After BWH, the effective overall hash power decreases to $1 - \alpha\beta$, so the new gain rate rises to $\frac{p’}{1 - \alpha\beta}$, with an increase of $\frac{\alpha \beta}{1 - \alpha\beta}p’$.

Similarly, we can define a similar “reward” proportion for attacking on another pool as $\lambda_2$.

Gains of the attacker

We assume attacker seeks maximum profit.

After joining the first pool, his work proportion is $\frac{\alpha\beta}{p + \alpha\beta}$, but the effective hash power of the first pool is still $p$ alone, as the malicious miner won’t submit any valid blocks. Therefore, he will in all gain $\lambda_1 \frac{\alpha\beta}{p + \alpha\beta} \frac{p}{1 - \alpha\beta}$ from the first pool.

Since he wants to maximize his profit, he won’t invest his money in other pools (otherwise, $1 - \lambda_1$ proportion will be taken away). He will use all his remaining $\alpha(1 - \beta)$ to mine solely. As a result, he will gain $\frac{\alpha(1 - \beta)}{1 - \alpha\beta}$ from that.

Finally, he will gain $\lambda_2 \frac{\alpha \beta}{1 - \alpha\beta}p’$ as the reward for betrayal.

In short, the overall gain of the attacker is:

The extra gain is:

As long as the following formula holds true, the selfish miner can make a profit from the attack.

which can be written in an informative form:

We will discuss the following formula in some special cases:

Genuine Bad Guy

$\lambda_2 \to 1$

In this case, as long as $\alpha \beta + p < \lambda_1$, the attacker can benefit. Since $\lambda_1$ is close to $1$, this will always hold.

No sponsorship

$\lambda_2 \to 0$

In this case, we need $\frac{\alpha\beta}{p} < \frac{\lambda_1}{1 - \alpha} - 1$. If $\alpha \le 1 - \lambda_1$, then it’s impossible for the miner to benefit from BWH.

Conclusion

In short, the more incentive (larger $\lambda_2$), the more beneficial the attack is.

Here are some figures: (y-axis is $\dfrac{\Delta G}{\alpha}$)

$\lambda_1 = 1, p = 0.2, \alpha=0.02$, where $\lambda_2 = 0, 0.2, 1$

$\lambda_1 = 0.9, p = 0.2, \alpha=0.02$, where $\lambda_2 = 0, 0.2, 0.9$

Better attack strategy

In fact, the miner may attack several pools. Consider $\frac{\Delta G}{\alpha\beta}$. Let $\gamma = \alpha\beta$, then we have:

This function is always descending with respect to $\gamma$, so the best strategy of a selfish miner is to split his attack across different mining pools. That is, he can attack not only the first pool but even the second pool, which rewarded him to attack the first pool. And the theoretical upper bound of his attack is

exactly when $\beta \to 0$.

$\lambda_1 = 0.9, p = 0.2, \alpha=0.02$, where $\lambda_2 = 0, 0.2, 0.9$. y-axis is $\dfrac{\Delta G}{\alpha \beta}$.

Possible Consequence of BWH

These dynamics create a “pool game”. If a pool $P$ is attacked, its miners’ revenue density falls. Rational miners might then leave $P$ for more profitable pools, further weakening $P$. If $P’$ gains (and pays the attacker), $P’$’s miners see higher revenue density. In equilibrium, pools could be tricked to attack others to gain an advantage, potentially leading to a “race to the bottom” where all pools lose.

Imagine there are multiple attacks between pools, it will result in a sharp decline in effective hash power: much of them are wasted in BWH.

Thus, BWH (classical or sponsored) undermines pool stability and Bitcoin stability: it can drive small pools out of business and cause mining resources to concentrate.

How to defend against BWH?

How to defend against BWH? The key insight is that: every miner could easily tell between a valid block and a normal share. As a result, they have the freedom not to submit those valid blocks, which may potentially harm those honest miners.

To fundamentally solve the issue, we should come up with cryptographic methods that guarantee the miner couldn’t tell between a valid block and a normal share. In this way, a miner who withholds any hash would not know if she was giving up a block or just an ordinary share, and he can’t selectively submit those non-block shares, which will stop BWH.

Method-01

In the paper “Bitcoin Block Withholding Attack: Analysis and Mitigation”, the following approach is proposed:

- The mining pool find a random string $r \in {0,1}^{z - z’}$ and another random string $s \in {0,1}^*$. Let $p = H(r || s)$

- Both $z’$ and $p$ is made public. Note that the protocol of Bitcoin needs to be changed in this case, as part of the header.

- The pool receives pool shares (partial proofs) from miners that its hash starts with $z’$ zeros.

- In the new protocol, a block is valid if it starts with $z’$ zeros, followed by a new nonce $r$. So a pool operator just need to check whether the next $z - z’$ bits of is $r$.

The approach above is as difficult as the old approach. Since the special nonce $r$ is sealed into $p$, which will be used in computing hash, it’s impossible to cheat by finding $r$ faster than brute force where:

Consequently, the target is quite similar: for a fixed $r$, find some nonce $n$ such that its prefix $z’ + z - z’ = z$ bits are fixed as $0^{z’} || r$. The key insight of this approach is that miners can’t find the $r$, so they can’t tell between shares and valid blocks. The verification of a block can be done by a pool operator.

Sadly, this approach requires modification of the protocol of Bitcoin.

Method-02

Let’s review the process of block withholding attack. How Can we directly detect that? A prominent feature of BWH is that: one never submits valid blocks. So, a naive idea is that: we reward those valid blocks. This is a naive fusion of mining pool and sole mining.

As long as submitting a valid block to the pool is more profitable than to its rival, a greedy miner will do the right thing.

We will introduce a potential workaround for BWH in the next slide.

Suppose the reward ratio for a non-block share is $\lambda_3$, the share-block ratio is $\mu = 2 ^{z - z’} > 1$, and the block reward ratio is $\lambda_4$. Assume the pool operator keeps the same proportion as before, then we have:

We can then let $\lambda_3 = \lambda_1 - \delta, \lambda_4 = \lambda_1 + (\mu - 1) \delta$.

The effective $\lambda_1$ now drops to $\lambda_3 = \lambda_1 - \delta$.\

Note that this is not a free lunch. As $\delta$ grows larger, it will degenerate to sole mining, which means the variance will also grow larger and unacceptable. It’s yet another trade-off.